How to achieve your educational goals

You’ve set ambitious goals for your school or district, but now comes the harder question: how will you actually achieve them?

In my work with school systems across the country, I’ve noticed a common pattern: teams often set goals and targets that make sense on paper, but then struggle to make meaningful progress.

They launch initiatives, buy programs, create task forces, study the data, but results barely budge.

It’s not for lack of effort. It’s because most improvement efforts skip the most important question in leadership: By what method?

This question sits at the center of the science of improvement. Goals don’t produce improvement. Targets don’t produce improvement. Hoping and trying harder don’t produce improvement. Only method produces improvement.

In this post, I’ll teach you a method that actually closes the gap between where your system is now and where you want it to be.

Why Method Matters More than Goals

A system performs exactly as it is designed to perform. If you want new results, you need a new design. This is why W. Edwards Deming emphasized that “a bad system will beat a good person every time.” No matter how motivated your team is, the existing structures, routines, and incentives will always dominate.

Most goals fail because leaders assume something like:

“If we set an ambitious target, people will rise to meet it.”

“If we monitor data more frequently, improvement will follow.”

“If we implement the right program, performance will increase.”

But without a method - a structured, scientific way of navigating from current conditions to the goal - teams either copy what others are doing, react to individual data points, or simply hope for the best.

You can do better than that. You can use a method grounded in how systems actually change.

Start with the System: Understanding Variation

Before any redesign work, you need to understand the system you’re working in. This starts with understanding variation, that is, the natural ups and downs that occur in every process over time.

For example, if your reading proficiency rate fluctuates between 50% and 60% year after year, the increases probably don’t represent improved performance. Similarly, the years where the results tick down don’t likely represent a decline in performance. Rather, all of the ups and downs taken together tell you what your system is capable of producing as designed.

This is why studying your variation over time is so important. It helps you answer three essential questions.

What is the system’s capability?

What results does your system produce on its best day and worst day?

How much variation exists?

Are outcomes fluctuating widely or fairly stable?

Is the system stable or unstable?

Are there special causes that require investigation, or is the system producing predictable results?

These three conditions - capability, variation, and stability - give you a realistic foundation for improvement. They tell you what is “within reach” versus what is more like a “moonshot” target.

Without this understanding, teams jump into solutions with no idea whether their actions can possibly produce the desired change. That’s why so much effort feels wasted.

Why You need a Model for Improvement

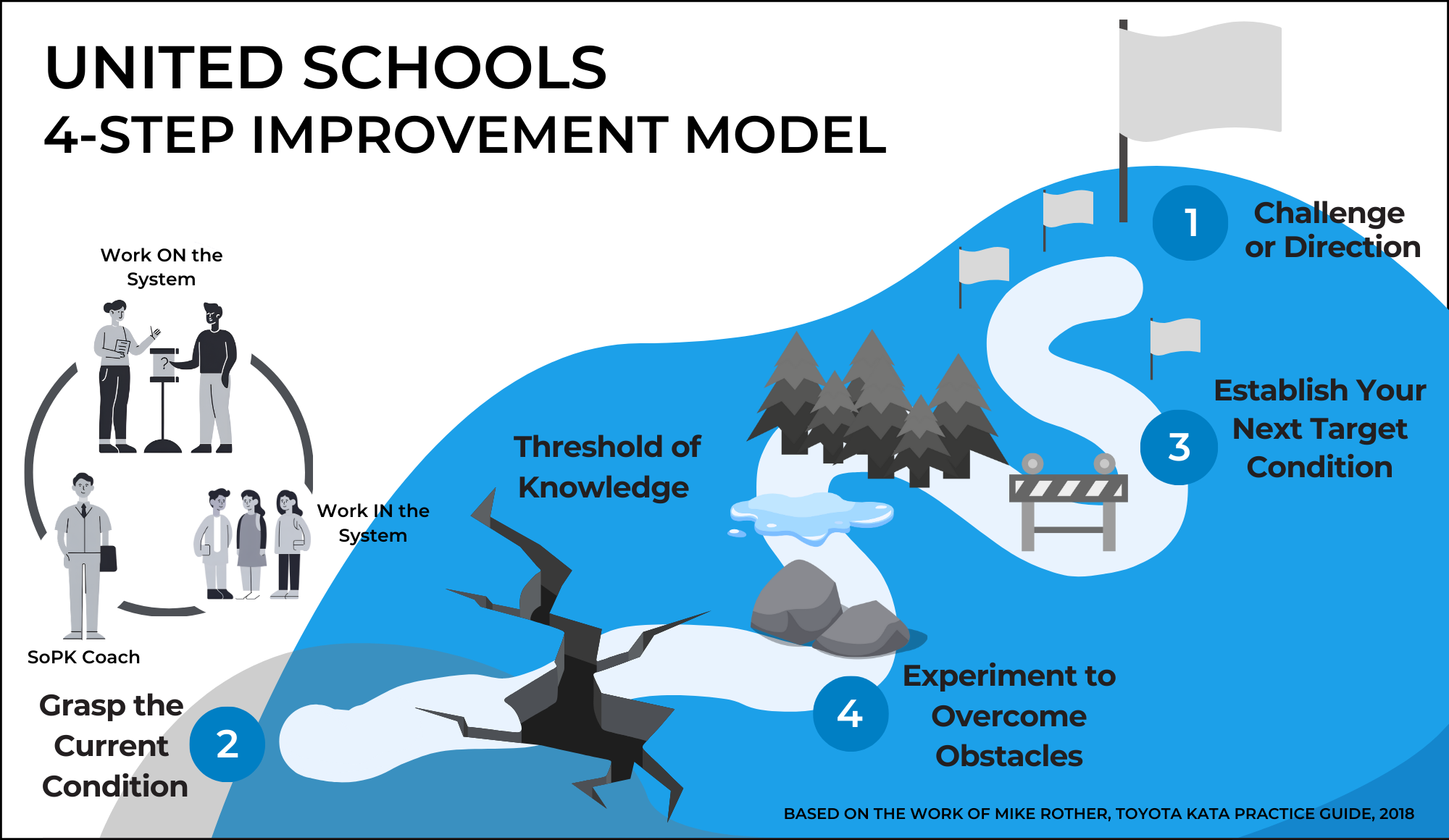

Once you understand your system, you need a method to improve it. At United Schools, we’ve begun to use a model influenced by Mike Rother’s Improvement Kata, which gives teams a scientific way of thinking and working.

This model helps us navigate the gap between our current and desired performance. This can aptly feel a bit like climbing a mountain, which is why the figure below is a useful visual to take in prior to moving on to the written description that follows.

4-Step Improvement Model

The Four Steps of the Improvement Model

Step 1: Define the Long-Term Challenge

This is your “nearly impossible” long-term aspiration, something that would differentiate your schools. A challenge typically has a time frame of six months to three years.

Examples:

Reduce chronic absenteeism to 5% (from 50%)

Reach a teacher retention rate of 85% (from 70%)

Ensure 90% of third graders meet literacy proficiency (from 50%)

This challenge is anchored in what your stakeholders need, not what your current system can produce.

Step 2: Understand the Current Condition

Before acting, study how the system currently operates. This means:

Plotting baseline data over time

Understanding variation

Identifying current capability and stability

Observing the work where it actually happens

This step represents our current knowledge threshold and contributes to how we define the next target condition we set.

Step 3: Set the Next Target Condition

A target condition is not an action step. It’s a description of the next level of system performance you aim to achieve in the near term (usually 1–4 weeks).

A good target condition describes:

What the process will look like

What outcomes it will produce

How it will operate differently

It’s ambitious relative to the current condition, but not so large that it becomes overwhelming.

Step 4: Experiment Your Way Forward

This is where improvement actually happens.

You run small, rapid Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles to test ideas, learn from them, and uncover obstacles. Each experiment moves you a bit closer to the target condition. When the target is reached, you set a new one. Over time, these short cycles accumulate into meaningful, sustainable system change.

Improvement rarely comes from a single breakthrough. It comes from disciplined learning over time.

And just as important as the steps themselves is who is involved in carrying them out. Successful improvement depends on having the right people engaged in the work.

The Roles that Make Improvement Possible

One of the most misunderstood aspects of school improvement is who needs to be involved. Improvement requires:

Students: the people inside the system who experience the inefficiencies

Teachers and school leaders: the people with the authority to change the system

Improvement advisor: a guide who understands systems, variation, psychology, and knowledge-building.

Most school teams overlook two of these groups, students and someone deeply trained in the science of improvement. These are the “secret weapons” of improvement work. When included, they dramatically accelerate learning and innovation.

Putting It All Together

Achieving your educational goals requires three ideas working together.

Big Idea 1: Understand current system performance before you make changes.

Big Idea 2: Goals don’t lead to improvement, sound methods do.

Big Idea 3: Improvement teams must include the three roles described above.

When you combine these three elements, you turn goal-setting into a disciplined journey of learning and progress. You stop reacting. You stop copying. You stop hoping.

Instead, you and your team move with purpose from where you are to where you want to be, one thoughtful experiment at a time.

***

Whenever you’re ready, there are 3 ways I can help you:

Do you have an improvement idea or question? I frequently share my experiences and resources with educators from across the world. I’d love to hear from you.

If you’re looking for a partner who understands the complexity of leading at scale and who can help you build a school system that improves over time, let’s set up a time to discuss your needs.

Win-Win is the improvement science text for education leaders. The aim of the book is to equip you with the knowledge and skills needed to use the System of Profound Knowledge, a powerful management philosophy, to lead and improve school systems.

***

John A. Dues is the Chief Learning Officer for United Schools, a nonprofit charter management organization that supports four public charter school campuses in Columbus, Ohio. He is also the author of the award-winning book Win-Win: W. Edwards Deming, the System of Profound Knowledge, and the Science of Improving Schools. Send feedback to jdues@unitedschools.org.